Deborah H. Drake and David Scott, The Open University

Image source: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-fq2W0bJAAKE/UEBDMMO_jyl/AAAAAAAADIk/EQx2Nm74aaw/s1600/buildcommunities.JPG

Image source: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-fq2W0bJAAKE/UEBDMMO_jyl/AAAAAAAADIk/EQx2Nm74aaw/s1600/buildcommunities.JPG

The prison industrial complex is large and growing. Prison building and expansion projects generate trade exhibitions, mail-order/Internet catalogues, and direct advertising campaigns that seek to engage architects, construction firms, investors, food, landscaping and plumbing supply companies, and other firms that specialise in fixtures and fittings for large industrial building. There is no doubt that the building of prisons creates a market of both temporary and permanent employment opportunities and can appear to increase the economic potential of the lucky local community that agrees to house a prison in their area.

If we look more carefully, however, at what the prison industry is, does and costs, prison building programmes become less attractive.

Economic benefits?

In 2003, researchers King, Mauer and Huling carried out the first study to use statistical controls to measure the effect of a prison on the local community, including its impact on the local economy and on employment and per capita income trends. The study examined 25 years of economic data for rural counties in New York and looked at 38 prisons located in upstate counties. The full report can be found here: Big Prisons, Small Towns: Prison Economics in Rural America, but some of their key findings indicated that:

- In 25 years, there was no significant difference or discernible pattern of economic trends between the seven rural counties that hosted a prison and the seven rural counties that did not;

- Residents of rural counties with one or more prisons did not gain significant employment advantages compared to rural counties without prisons;

- Unemployment rates moved in the same direction for both groups of counties and were consistent with the overall employment rates for the state as a whole;

- During the period from 1982 to 2001, these findings are consistent for the three distinct economic periods in the United States, and in fact, the non-prison counties performed marginally better in two of the timeframes;

- Counties that hosted new prisons received no economic advantage as measured by per capita income;

- From the inception of the prison building boom in 1982 until 2000, per capita income rose 141% in counties without a prison and 132% in counties that hosted a prison.

When comparing new prison towns across the USA with other towns of a similar size, Besser and Hanson also found that there was no discernable differences between unemployment rates between 1990 and 2000 between the towns. Like King et al., they concluded that building a new prison did not create jobs for local unemployed people.

At a similar time to the above studies there was a further comprehensive analysis of prison towns in the USA which explored the impact of prison building and job growth in the USA from 1976-1994. In a follow up study, expanding the period to 2004, the evidence shows that rather than promoting economic prosperity and creating new jobs, in both urban and struggling rural communities, prisons may actually impede employment growth. Hooks et al. (2010) conclude that ‘our research into employment growth suggests that prisons are doing more harm than good among vulnerable counties’. The reasons why prisons failed to provide economic stimulus to the local economy included:

- There were not necessarily new jobs as prison officers moved from other prisons to fill the new jobs;

- There was the possibility of adverse local impacts of prison labour through prison industries and low cost prisoner labour;

- There may be a paucity of local skills and direct connections to the services required by the new prison.

Despite the initial promises of economic prosperity that it is assumed can be made from opening a prison, these promises are not borne out in practice. Moreover, no prison can generate income or be ‘cost efficient’. Prisons cost a lot to run and they drain resources from other areas of social life, such as hospitals, schools, housing or social services. Investing, instead, in local services, programmes, health and education sectors or other community-focused initiatives would be a far better use of resources and, incidentally, are more effective than prisons at PREVENTING crime, as opposed to responding to it after the fact, as prisons do. That is, the idea that increased funding for police and a larger prison estate will solve and economic problems is a myth.

Human costs

Setting the obvious economic shortcomings to prison building aside, let’s think for a minute about the human and social costs of prisons. Firstly, there is no evidence that prisons effectively do very many of the things they claim to do. This has been repeatedly demonstrated through society’s years of experimentation with the prison and in numerous academic considerations (see Mathiesen, 2000 for example). Prisons do not deter crime, they do not ‘rehabilitate’ prisoners, they do not prepare people well for law-abiding lives in the community. The only functions that prisons serve well relate to pain and suffering: they deliver punishment and incapacitation and, symbolically: they are a demonstration that ‘justice’ is being done and that the ‘system works’.

Prisons are places that cast out, ostracize and de-socialise members of our communities and society. They are places that take things away from people: they take a persons’ time, relationships, opportunities, and sometimes their life. Prisons constrain the human identity and foster feelings of fear, anger, alienation and social and emotional isolation. For many prisoners, prisons offer only a lonely, isolating and brutalising experience. At best, prison environments are dull and monotonous living and working routines depriving prisoners of basic human needs. At worst, they are places of violence, suffering and physical and psychological pain. Combined with saturation in time consciousness/awareness, these situational contexts can lead to a disintegration of the self and death (Scott, 2016).

For prison officers and other prison staff prisons are toxic environments. Stress, illness and sometimes also death are perils of prison work. Prisons do not encourage health, education, renewal, care, compassion, decency or any of the other values that most societies and individuals cherish. Instead, they stimulate humiliation, illness, anger, hatred and punishment. They are places that encourage moral indifference between staff and prisoners, where the shared humanity of prisoners and staff is neutralised and where the pain and suffering of one another is ignored.

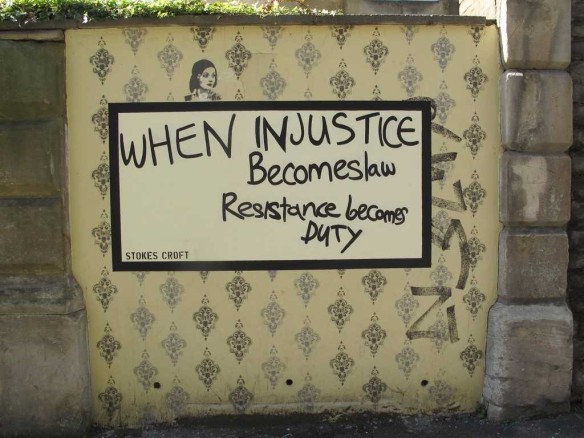

Rather than investing in criminal justice and building more prisons in a time of economic austerity, we should be demanding investment in our communities, in our social lives and in programmes that centralise the importance of social justice – for everyone.

This article first appeared on the Reclaim Justice Network site, at: https://reclaimjusticenetwork.org.uk/2017/06/29/build-communities-not-prisons/