Dave Middelton, The Open University

What sustains a Government in power? Having the number of MPs to win votes seems pretty important you might think (although the Tories threw away a working majority and now have a very narrow lead and need the support of the DUP). As does having support in the country (see recent YouGov poll here.) However, neither of these can quite explain the success of the current Tory Government who should be in far more electoral trouble than they are. Of course, some people will point to a divided opposition and this remains true.

But that is to assume that the Tories themselves are united which is clearly not the case. What is sustaining the Government currently is a politics that can best be described as petty and vindictive. Unfortunately this pettiness and vindictiveness has plenty of support throughout the country and can be seen in many policies introduced over the past 20 years or so.

The most recent example is the so-called Windrush scandal in which the Home Secretary has been made to resign over an overtly racist policy introduced by her predecessor with the explicit aim of “encouraging” people to leave the UK. (Here is the BBC doing their best to emphasise the personal tragedy for Amber Rudd).

The hostile environment policy introduced by Theresa May when she was Home Secretary was a policy that was racist both in its intent and application. What is so disappointing is that this policy received no real critical examination in the media (and very little in Parliament) until it emerged that black citizens, who clearly had the right to be in the UK, were affected. This came to light following an investigation by Guardian journalist Amelia Gentleman.

The policy and its political fallout is largely treated as if it was an accident, an oversight, and even a personal tragedy for Amber Rudd. But, it was not an accident it was a deliberate and sustained attempt to create an atmosphere of fear and intimidation toward black citizens in a somewhat vain attempt to meet targets which despite the lies to the contrary clearly existed.

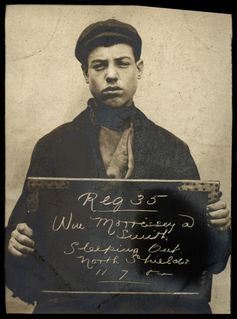

It is not clear how many ‘illegal’ immigrants there are in the UK (the Office For National Statistics warns that methods of calculating the number are seriously flawed), but what is clear is that this policy and its accompanying ‘leave now’ vans were designed to intimidate a particular community. Why is tackling so-called ‘illegal immigration’ seen as so important to a Government that surely has more important things to worry about?

Theresa May in defending the policy constantly ignores the human suffering she has caused preferring to remind us that there are people in the UK illegally. It is an obfuscation that plays well with the Tory grassroots and the mass media and it completely misses the point. Although the right wing press play along. (Heres the Daily Mail’s reporting of May’s defence of the policy.)

There is no need to consistently victimise people who do not have the means to fight back. This is a policy based on a vindictive and empathy lacking political elite whose own lives are rarely, if ever, touched in a negative way by the programmes they introduce.

The “hostile environment” policy is no aberration. The disabled, single parents, unemployed, refugees, those who rely on benefits have all been treated, in one way or another, to versions of the hostile environment.

The Ken Loach film I, Daniel Blake showed brilliantly how difficult it has become in the UK to claim benefits.

Rather than social security, as we used to call it, being a safety net for those in need it has become a bureaucratic means of humiliating individuals whose only crime is to have fallen on hard times.

We now know that as a result of the stress caused by the ‘hostile environment’ policy more than one person was driven to suicide. The website Calum’s List lists 63 known cases of deaths attributable to cuts in benefit. The figures for the number of suicides attributed to austerity programmes and particularly those involving the targets to reduce benefits are difficult to ascertain as coroners rarely report “Government policy” as a cause of death, but a recent report suggested that at least 81,000 people have taken their own lives shortly after receiving suspensions to their benefits (https://archive.is/zhvCc#selection-597.0-605.36).

Perhaps this will be more shocking if we name some of these people. On November 17th 2017 the Manchester Evening News reported that 38-year old Elaine Morrall died in her freezing home after her benefits were stopped. (Manchester Evening News)

On 10thDecember 2017 The Independent reported that 32 year old singer-songwriter Daniella Obeng died in Qatar where she had gone to find work after her disability benefits were stopped. (Independent)

On June 22nd 2017 the Disability News Service reported on the case of Lawrence Bond a disabled former electrical engineer who died of a heart attack after being told that he was fit for work. (Disability News Service)

But, it is not just the suicides, though if I were a Government Minister I would not want them on my conscience (assuming, of course that Government ministers actually have consciences). The strain that ordinary people are placed under as a result of being denied benefits or being investigated by the Home Office is cruel and usually unnecessary (this blog shows the effect on some of the people who get caught in this bureaucratic trap). For the victims of these deliberately created hostile environments life becomes like living in a Kafka novel.

Socialists are often accused of pursuing a politics of envy and yet the real politics of envy is not those who seek a more equal society but those who seek to maintain a society which is structurally unequal. The vindictiveness of those who enact laws and regulations aimed at the most desperate and vulnerable members of our communities is a national scandal that the occasional ministerial resignation does nothing to change.

Whilst the papers and broadcast media were full of pity for Amber Rudd and enthusiasm for her successor, they fail to notice the number of people who are the real victims of the policies Amber Rudd, Sajid Javid and Theresa May are responsible for enacting. And, whilst it is tempting to think that a change in government would end the hostile environment for ethnic minorities, the disabled, the poor and the vulnerable in our society ultimately we need a change in our culture which will probably only occur in a completely different type of society from the one we are living in now.

This post was originally published on Dave Middleton’s blog Thinking and Doing, at: http://davemiddletons.blogspot.co.uk/2018/05/government-policy-is-characterised-by.html