Abigail Rowe

International Centre for Comparative Criminological Research

The Open University

December 2014

At the end of October, amid a flurry of controversy, the Home Office published the findings of an international comparison of the policies adopted by thirteen countries to tackle drug misuse and dependency. The study, which has been widely hailed by commentators as demonstrating that a ‘criminal justice approach’ to drugs is ineffective, was a concession to the Liberal Democrats, who had promised a liberalisation of drugs legislation in their 2010 manifesto and have since been arguing for a Royal Commission on drugs. Several days later, however, Liberal Democrat Minister Norman Baker resigned from his post in the Home Office, alleging that Home Secretary Theresa May had blocked publication of the report for several months, and describing working with her as ‘a constant battle’. The controversy within the Home Office over the report has brought the contrasting attitudes of Liberal Democrats and Conservatives around drugs policy into wider public consciousness, but has also highlighted the uneasy relationship between politics and criminal justice policy.

Although the published study contains no overarching conclusions, the evidence it presents demonstrates that there is no consistent relationship between the severity of a country’s drugs laws and the prevalence of drug use, addiction and associated harms among its population. A comparison between the approaches of Portugal and the Czech Republic exemplifies this. While both have effectively decriminalised the possession of a small amount of any drug for personal use, Portugal has seen improved health outcomes and falls in levels of drug use and drug-related deaths, while in the Czech Republic following decriminalisation, rates of marijuana use remain among the highest in Europe, health outcomes have worsened and drug-related deaths have increased. Sweden, on the other hand, which takes a stringent criminal justice approach to psychoactive substances, has relatively low levels of drug use, although not significantly lower than in some other countries taking different approaches. The Home Office study, then, quite clearly demonstrates that the severity of the sanctions in place for drug possession and use doesn’t determine whether or not a country will have a drug problem. That is, whatever the strengths or weaknesses a country’s drug strategy may have in managing the risks and potential harms of drug use, whether or not the trade in and/or use of psychoactive substances are criminalised is clearly not key to managing the problem.

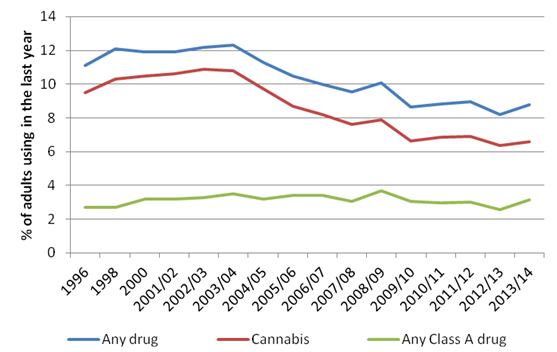

Despite this, the Foreword to the report – authored, as is usual in government documents, by the politicians who commissioned it rather than researchers who conducted the study – introduces the findings with the assertion that what they primarily show is that different policies work in different contexts and wholesale policy transfer is clearly impossible. More than this, it claims that, read in the context of long-term declining drug use in the UK, the study demonstrates that the Government’s ‘balanced and evidence-based drugs policy’ is sound. This indicates a clear resistance to the opening of a debate around reform of the drugs laws.

Source: Home Office (2014). Despite the government’s claim that a long-term decline in drug use indicates that government policy is working, most of the decline is accounted for by a fall in cannabis use, while the use of Class A drugs has been stable for two decades.

Theresa May has offered little comment on either the report or Baker’s noisy resignation. As the story began to gain momentum in the press, however, the Prime Minister intervened with a clear dismissal of the possibility of any relaxation in the drugs laws. He offered little engagement with the evidence presented in the report, but fell back on clichés of ‘common sense’ and the moral claims of parenthood: the criminalisation of drug use would remain in place because ‘as a father of three children’ he did not want to ‘send a message that somehow taking these drugs is okay and safe’, and that decriminalisation would ‘add to the danger’ posed by psychoactive substances – this last point despite the clear evidence of the report that the ‘message’ sent by the law is not the significant factor in determining the prevalence of drug use. Furthermore, not only would the policy of criminalisation not be relaxed, it would be extended to cover substances currently known as ‘legal highs’.

Cameron’s argument rests on the value of the drugs laws as symbolic, and – supposedly – deterrent. This focus on the immediate harms and risks associated with the consumption of drugs neglects the myriad of other, state-sponsored, harms generated by criminalisation, which range from the violence and instability caused by the illegal multi-billion dollar international drugs trade, to the harms to individuals and communities that come with the imposition of criminal justice sanctions on users. This narrow conception of drug-related harm and the resistance to an evidence-led approach to drugs policy by UK politicians has history over successive governments of different political stripes. In 2000, for example, the Blair government greeted the recommendations of the Runciman Commission to downgrade the classification of ecstasy and cannabis, and to treat possession of the latter as a minor civil offence , with panic, conceding only the downgrading of Cannabis from Class B to Class C when it became evident that The Daily Mail had received the report with approval rather than the expected outrage. Eight years later, however, and against scientific advice, Gordon Brown’s administration reversed that decision and sacked senior drugs advisor David Nutt for criticising the move as being without foundation in evidence. For Guardian commentator Simon Jenkins, who was a member of the Runciman Commission, government resistance to an evidence-led drugs approach to drug use represents a failure of drugs politics rather than drugs policy.

A continuation of current policy means a reaffirmation of the government’s commitment to criminal justice sanctions for those convicted of dealing in, or possessing, illegal drugs. This group accounts for a substantial proportion of the prison population. 2013 Ministry of Justice figures show that 14% of men in prison, and 15% of women were serving sentences for drug offences. This, however, masks the much larger number of convicted prisoners whose convictions were indirectly drugs-related (i.e. not for possession or supply of drugs themselves): in the same year, 66% of female and 38% of male prisoners reported that the offence for which they had been sentenced was committed to fund their own or someone else’s drug use. Not only does it draw very large numbers into our prisons, our current criminal justice paradigm serves those with problems of substance abuse and their communities very poorly. For example, illegal drugs are disproportionately used by minority, marginal and disadvantaged groups – young people, those from ethnically mixed backgrounds, gay and bisexual men and women, and people living in areas of relative deprivation. Meanwhile, while members of Black and Minority Ethnic groups use drugs at a lower rate than the population as a whole, for example, they are more often stopped and searched under drugs laws, and receive more severe sanctions for drugs possession offences when convicted.

Not only is the criminal justice approach to the use of psychoactive substances fundamentally problematic, the government’s reaffirmation of its commitment to maintain the status quo in drugs policy comes at a time of mounting strain in the criminal justice system. At close to 86,000, the prison population in England and Wales is not far from its historic high, and in a context of budget cuts, reduced staffing levels and prison closures, the consequence of this is overcrowding and reduced levels of purposeful activity for prisoners. The prison population is being held in facilities not designed to accommodate their numbers, and concentrated into larger and larger prisons, which are known to be less safe. These conditions cannot ensure basic safety, much less deliver the government’s promised ‘rehabilitation revolution’. The number of assaults recorded against both staff and prisoners has increased and, most worrying of all, suicides among prisoners have risen sharply over the last year: clear indicators of a prison system in crisis. The Chief Inspector of Prisons, Nick Hardwick, has issued a clear warning: either the prison population must fall or prisons must be better funded. The Home Office report demonstrates clearly that prohibition is not a meaningful deterrent to drug use. Neither is prison an effective place to deal with problems of addiction: drug use (including first use of heroin) among prisoners is high while the current trend towards larger institutions exacerbates these risks, as prisoners in large establishments are more likely to know how to get hold of drugs, but less likely to know where to get help with problems of addiction.

Over the the last month, the Coalition row over the government response to the Home Office report, and the crisis of rising suicides, overcrowding and violence in our prison system have sat cheek-by-jowl in the headlines. We have a bloated prison system that – while public and welfare services are being cut elsewhere – we can ill afford, and into which we channel thousands of men and women each year, disproportionately from marginal and disadvantaged sections of society, where their social disadvantage is compounded and physical and psychological well-being profoundly threatened. While there is no denying the harms generated by substance addiction, all a criminal justice approach can offer us is what Willem De Haan has described as ‘spiralling cycles of harm’. We know better than this, and it is in all our interests to start doing better.